Casey Kaplan

Eyes and Ears

The audio, visual world of Diego Perrone

December 15, 2014

By BARBARA CASAVECCHIA

‘One Of These Days’, the opening track on Pink Floyd’s 1971 album Meddle, is an instrumental, save for a single sentence spoken by the drummer Nick Mason: ‘One of these days I’m going to cut you into little pieces.’ Mason’s voice is distorted and slowed down to such a degree that it sounds like that of an evil cartoon character, and it’s hard to understand what he says, though his menacing tone is clear enough. There is an iridescent, psychedelic colour photograph of a brownish thing against a turquoise background on Meddle’s cover (designed, as numerous other Floyd covers were, by Hipgnosis); only once you open the gatefold sleeve does it become apparent that this image is actually a close-up of an ear underwater, surrounded by circular ripples that look as if they’ve been caused by sonic vibrations. Discerning whether this ear is attached to a body or has been cut off is left to the viewer’s imagination.

A self-confessed teenage fan of Pink Floyd, Diego Perrone has always been fascinated by our inborn capacity to apprehend sound, and the ways in which it can be distorted and contorted. Perrone’s approach to making art – from video and digital animation to painting and cast sculpture – is defined more by how a work is perceived visually than aurally. And yet, during a recent conversation, he claimed never to have thought about this emphasis on the auditory dimension of his work. This is surprising given the abundance of acoustic reverberations in his practice, which now spans two decades. When Meddle came out, Michael Watts, reviewing it for the music journal Melody Maker, described it as ‘a soundtrack to a non-existent movie’; inversely, it is tempting to describe Perrone’s works as visual evocations of imaginary soundtracks. Like film scores, they are made to conjure a set of immediate emotional responses: tension, fear, suspense, unease and wonder, filling the void that separates the object from its beholder with aural ghosts. It is precisely this sensitive space that the artist seems most interested in shaping. The word ‘sensation’, after all, derives from sentire, a Latin verb still used in the artist’s native Italian to describe the perception of both emotions and physical sensations, including hearing.

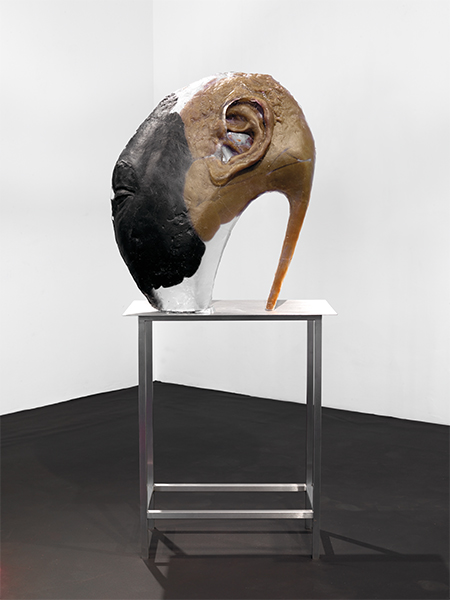

As organs isolated from the rest of the body, ears have been a recurrent, eerie subject in Perrone’s work since 1995, when he sculpted his first translucent, life-size pair from horn (Untitled). A decade later, he created two large sculptures in polystyrene and plaster (Untitled, 2005), reproducing the ear’s entire structure, from the cartilage of the outer shell, or pinna, to the inner cochlea, in which sound is converted into the electrical impulses that are then transmitted to the brain by the auditory nerve. In recent years, Perrone has been working on a series of experimental glass castings of ears (Untitled, 2011–ongoing), the hooked and beaked inner conduits of which seem to erupt in silent screams, as well as to crystallize the process of auditory perception. The visual appeal of these works – all unique pieces in candy pinks, light greens, icy whites and muddy browns – is enhanced by the artist’s use of a combination of the ancient technique of lost-wax casting and new, high-tech versions of traditional glass-paste techniques (developed in collaboration with Vetroricerca Glas & Modern in Bozen/Bolzano, Italy), so that the old and the new merge in uncanny ways.

Perrone’s most recent exhibition, ‘Void-Cinema-Congress-Death’, at Massimo De Carlo in London, opened with a small, framed, red-biro drawing of a person’s ear – filling the silhouette of one of Alexander McQueen’s lobster-claw-shaped ‘Armadillo’ stilettos – installed in the middle of the gallery’s large, street-facing window (Untitled, 2013). Inside, two large pieces in cast glass (both Untitled, 2014) featured the same shape, each with a gargantuan ear protruding from its centre, with the long, thin stiletto ‘heel’ standing in for the auditory tube. Made using solid rather than blown glass, these two sculptures have a hard, mineral texture. A red dragon screen-printed onto the otherwise black floor lent the installation a dark undertone. Downstairs, Perrone coupled a series of biro drawings of heads with a new body of handmade, bas-relief works in sheet iron, white synthetic gypsum and black PVC (all Untitled, 2014) depicting empty cinema chairs protruding from the walls like bulky ghosts. The artist describes these chairs as the epitome of inexpressive design: cheap, mass-produced items that are usually seen in their hundreds or even thousands, but which people mostly don’t acknowledge. ‘I was thinking of Muzak, which doesn’t require any effort to be listened to,’ says the artist, and ‘of Brian Eno’s Music for Airports (1978). The idea of a constant, ambient sound that wraps itself around you and invades your space’.

Easy Listening is not a genre one would normally associate with Perrone. The mp3 he selected for his participation in the audio section of ‘After Nature’, a group show at New York’s New Museum in 2008, was a reading of H.P. Lovecraft’s novel The Beast in the Cave (1905), the story of which unfolds in a pitch-dark cave, amid terrifyingly unplaceable echoes. For a 2010 solo exhibition at the Brodbeck Foundation in Catania, not only did Perrone create Pendio piovoso frusta la lingua (Rainy slope whips the tongue, 2010) – a sculpture that attempts to embody the roar of a landslide and the physical impact of fear on the body – but to accompany it he asked electro musician Tommaso Previdi to create a drone akin to that of a natural disaster, and amplified it through a 30-metre-long tubular structure, so that the entire gallery space vibrated threateningly.

Perrone’s private horror-film collection is notoriously wide-ranging: from Tobe Hooper’s classic slasher The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) to David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983), and from Shinya Tsukamoto’s epic Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989) to Lars von Trier’s The Kingdom (1994). One of the artist’s personal favourites is Profondo Rosso (Deep Red, 1975), Dario Argento’s cult movie shot in Turin, which has an atmospheric soundtrack by the Italian prog-rock band Goblin, who were a substitute for Pink Floyd after Argento was unable to persuade them to participate. (The film’s feast of screaming mouths, gory killings and Technicolor blood-dripping scenes come courtesy of the special-effects skills of Carlo Rambaldi, who went on to create E.T. in 1982 for Steven Spielberg.) Perrone paid his dues to abjection early on with the short video Angela and Alfonso (2002), in which the screaming female protagonist voluntarily and inexplicably submits herself to her boyfriend’s attempts to slice off one of her ears – a professionally orchestrated bloody mess. An even earlier piece, I Verdi Giorni (The Green Days, 2000) is a short colour animation of a group of kids punching and harassing each other, laughing and shouting – a sort of half-playful, half-painful self-portrait. (The distorted voices were those of Perrone himself with Massimiliano Buvoli, Alessandro Ceresoli and Patrick Tuttofuoco – all artists he had studied with at the Brera Art Academy in Milan.) Usually screened with the soundtrack blaring, I Verdi Giorni is impossible to ignore. When reviewing it in 2002, while it was on show at Casey Kaplan, The New York Times critic Roberta Smith noted that it ‘gives unbroken tension and screaming close-ups a comic edge’.

As fond of Jim Shaw as he is of the Slacker generation, Perrone appropriates ‘high’ and ‘low’ art-historical icons and techniques with a degree of anarchical freedom. And, despite the perennial critical reading of contemporary Italian art as stemming from Arte Povera and Conceptualism, he found his roots elsewhere, in a broad range of historical references, from Umberto Boccioni to Mario Sironi, and with a distinct perspective on Italian identity. In Totò nudo (Totò Naked, 2005), he transformed Totò – an actor who became such an icon of Italian postwar comedy that Pier Paolo Pasolini cast him repeatedly in order to ‘de-codify’ him, as the director once explained in a famous interview – into a 3D digital animation undressing in a forest at twilight. Gradually, Totò’s clothes fall on the snow-covered ground until his ageing body is full-frontally naked: vulnerable and embarrassed, he is nonetheless now freed from his habitual Chaplinesque costume.

Perrone is also at ease with older masters. For Idiot’s Mask (Adolfo Wildt) (2013), he used airbrush on pvc to reproduce a series of snapshots he had taken with his mobile phone (light reflections and glitches included) of a marble bust by Adolfo Wildt, the Art Nouveau father of Italian Modernist sculpture. For the Venice Biennale in 2013, curated by Massimiliano Gioni (who also selected Perrone for his Italian Pavilion, La Zona, ten years earlier), he presented a twin set of sculptures, exhibited side by side on metallic poles, entitled Vittoria (Adolfo Wildt) (2013). Again, the work was inspired by a Wildt marble sculpture: La Vittoria (Victory, 1918–19), an odd winged head with an open mouth, as if singing, which was created for the Palazzo Berri Meregalli in Milan. Perrone reproduced the historic work in two different ways: firstly, as a lost-wax casting made with a mix of resin and fibreglass, producing a very porous surface, yet a fluid and seamless overall outline; secondly, as a hand-sculpted form comprising welded blocks of industrial pvc, an ‘old school’ plastic with the same weight as marble and with a similarly polished, rock-like surface. Produced at different paces, using diverse but equally labour-intensive methods of construction, both works caused evident distortions to the original shape. But, as with music, so with art: like all good cover versions, Perrone’s Vittoria pieces are unique in their own right, obtained by morphing the past into a present ‘version’. I love to think of them as ‘scream queens’, demanding attention against the white noise of visual indifference.