Casey Kaplan

Uncanny Nostalgia: Igshaan Adams’ “When Dust Settles”

A review by Courtney Drysdale

10 July 2018

Igshaan Adams was brought up in Bonteheuwel, Cape Town by his Christian grandparents, but he is a practicing Muslim using his works to identify and comment on religion and sexuality. Adams often examines cultural hybridity and spirituality through the subtle interpretation and contestation of social and political boundaries. His new body of work, produced for the Standard Bank Young Artist Award is titled “When Dust Settles,” and was shown for the first time in the Gallery in the Round during this year’s National Arts Festival in Grahamstown.

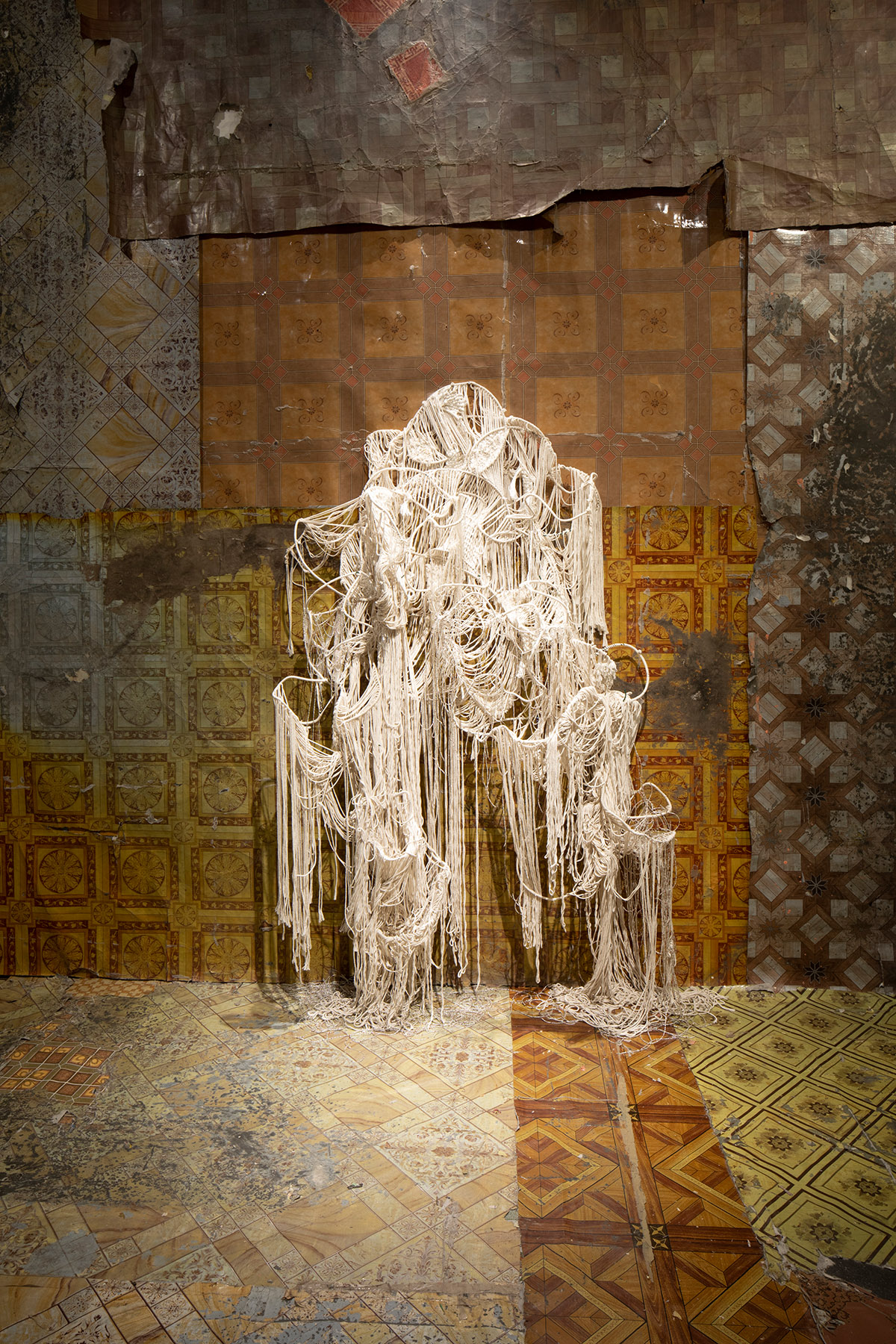

The exhibition consists of large-scale sculptures made of wire, beads and white cotton thread, with others including face cloths. A large installation incorporates vinyl, layering the walls and floors with used and well-worn linoleum floor panels. The title itself is indicative of reflecting back on previous practices through new perspectives, with two performances involving his mother and brother that explore healing and catharsis.

Click here to continue reading