Casey Kaplan

Giorgio Griffa

CENTRE D’ART CONTEMPORAIN GENÈVE

September 2015

By Molly Warnock

IT HAS BEEN more than fifty years since Donald Judd famously declared “European art” over and done with. The American artist’s pronouncement, voiced in an oft-cited 1964 conversation with Bruce Glaser and Frank Stella and grounded in his perception that the work of the Continent’s painters was woefully mired in the past, marks a particular tipping point in transatlantic rivalries; until recently, a similar bias tended to color most accounts of art since Minimalism. Artists abroad, it was often suggested, simply missed the developments of the 1960s—not least by continuing to paint. Yet the past two decades have seen important shifts in thinking. Thanks to recent scholarship, as well as some remarkable exhibitions—I think especially of the seminal “As Painting: Division and Displacement,” held at the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio, in 2001, which helped call attention to a range of French practices in particular—we are seeing a veritable upsurge of interest in what one might call “Minimalism-adjacent” painting in Europe in the 1960s and ’70s. Recent gallery shows in New York of work by Simon Hantaï, Supports/Surfaces, and Niele Toroni (who is also receiving institutional attention), among others, are to be seen in this light, and so, perhaps, is renewed interest in that city and elsewhere in roughly contemporaneous achievements by Italian painter Giorgio Griffa.

Now in his seventy-ninth year, Griffa was born in Turin and began showing there in 1968. His emergence coincided both with an explosion of extrapictorial practices and with the Italian Hot Autumn, a period that saw many younger artists—including those associated with Arte Povera—rethinking the premises and the social standing of their work. Griffa was no exception: In a recent interview with curator Marco Meneguzzo, he recalls his contemporary opposition to traditional modes of authorship, and his desire to ground his practice in notionally anonymous signs: “That my ‘little rags’ should get around was a revolutionary condition not lived as a ‘terrorist bomber’ but as a ‘housewife.’” (Typically for Griffa, the artist’s somewhat elliptical phrasing places him in a decidedly passive posture, grammatically as well as by virtue of the thematic contrast between incendiary partisan and notionally unassuming homemaker.) Nonetheless, as the reference to “little rags” suggests, he remained—and remains to this day—doggedly committed to painting, and to the “humbling” of gesture he believes is uniquely capable within that medium. His canvases with highly reduced signs did in fact circulate, appearing in some of Europe’s most prestigious galleries, as well as in the 1978 and 1980 Venice Biennales. Institutional recognition, however, long eluded him.

An important survey at the Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève therefore signals a sea change in the painter’s international reception. Curated by CAC director Andrea Bellini, and following in part on the critical success of the artist’s 2013 exhibition at Casey Kaplan in New York, it is the first of four exhibitions to be held between May 2015 and September 2016, preceding affiliated shows at Bergen Kunsthall in Norway, the Fondazione Giuliani in Rome, and the Museu de Arte Contemporânes de Serralves in Porto, Portugal. These forthcoming projects will, one hopes, highlight different facets of this expansive body of work. In the meantime, Bellini’s presentation offers an illuminating overview of the painter’s corpus, as represented by just thirty-five carefully chosen and perfectly installed paintings. More than half of the featured works, significantly, date from the ’60s and ’70s, and these emerge as integrally involved in a broader, international transformation of painterly practice.

Developments in France, in particular, offer ready references for the work in the galleries. Griffa’s emphasis on repeated, seemingly neutral gestures recalls the positions staked out publicly as of 1967 by Daniel Buren, Olivier Mosset, Michel Parmentier, and Toroni, though the Italian painter varies his mark from one work to the next. At the same time, his commitment to the subjective qualities of color (Griffa’s tones are always mixed, so as to signal the residue of authorial choice) and technique of staining unprimed cloth with acrylic pigment suggest affinities with Supports/Surfaces and especially the work of Claude Viallat; in fact, something like the latter’s own painterly device—the bean-shaped sign he adopted in 1966—appears in certain works by Griffa of the ’70s. The painter’s programmatic recourse to unstretched canvas and the traces of folds that result from the works’ storage, a defining feature of his practice since 1968, only reinforce the sense of proximity to Supports/Surfaces, placing his canvases on a par with other, decidedly physical, and, as it were, “modest” linens produced by artists in that group: Think of Noël Dolla’s marked and stained tea towels and floor cloths of the later ’60s and ’70s or Patrick Saytour’s use of tablecloths, curtains, and blankets, among other supports, throughout the same period.

Yet Griffa’s paintings appear open-ended, indeed deliberately suspended, in ways that set them apart. Unlike the majority of work produced by his French peers, the artist’s canvases are never allover, nor do his motifs produce the effects of optical expansion, of seeming endlessness or boundlessness, so often evoked by Viallat’s fields in particular. Rather, he interrupts his marking midstream, always leaving a significant expanse of blank canvas—a gesture his writings and interviews suggest is rooted in resistance to utopian attitudes and a concomitant desire to foreground the finitude of action, its inevitably situated and oriented nature, within the limited arena of the painting itself. The first canvas in the Geneva show, Da sinistra (From the Left), 1969, announces this quality of Griffa’s work. Short strokes of rose-colored paint in irregular horizontal rows proceed, writing-like, from the canvas’s left edge, barely penetrating the vertical, page-like expanse before breaking off and commencing anew—as if to underscore the seemingly straightforward but in fact exceedingly fragile task of putting one touch after another, of remaining sufficiently present to the work to construct it bit by bit. (Many works show him concluding not simply with the terminal line in a series of repeating signs, but by breaking the final trace midway.) Also relevant, one suspects, are the etymological associations of sinistrality with awkwardness—the idea of the “gauche” that Roland Barthes would soon make central to his account of Cy Twombly’s work—on the one hand (those repeating, deliberately “artless” signs), and femininity on the other (the gendered connotation of their pinkish tone).

Griffa’s interest in the limits of agency informs a broader characteristic of his practice through at least the later ’70s: the centrality of line. His painting is essentially colored drawing, and it is consistently keyed to a sense of physical traversal through time and space: line as ductus, not contour. Although the signs sometimes break across a crease in the canvas—a phenomenon that, as Barry Schwabsky has noted, suggests that the fold preceded the trace—each gesture nonetheless appears to result from a single movement, a unique kinetic impetus. Yet in each instance, the use of staining suggests a trajectory integrally conditioned by its material circumstances. (Morris Louis is among Griffa’s avowed references, and his stripe paintings in particular stand behind much of the work in Geneva.) The signs at the CAC vary: Linee orizzontali (Horizontal Lines), 1974, stands in for the hundreds of paintings of strictly left-to-right lines Griffa completed in his early years, while others run a gamut from the erratic paths of Linee policrome (Polychrome Lines), 1973, to the controlled curves of Dalla terra al cielo (From Earth to Heaven), 1979. One clearly feels the authorial decision or governing “rule” behind each mark, yet the edges of the lines bleed irregularly into the support, just as one color seeps unpredictably into another where the traces cross. Elsewhere, the artist deploys thicker, variously oriented segments that function as post-Matissean colored shapes, as in Obliquo (Diagonal), 1976, or Sei colori (Six Colors), 1977. Here the uneven saturation of the pigment is even more pronounced, reminding us that while the painter chooses how to proceed, the results of that decision are not entirely up to him.

The folds that mark Griffa’s support foreground the physical context for action and also effectively constitute another system of drawing. Folding, as this painter practices it, appears as a deductive process par excellence: His divisions proceed from the literal putting-in-contact of opposed corners and edges; they measure and map the support from which they derive. The results vary accordingly—from a simple vertical bisecting a small, markedly horizontal support (IN[VISIBLE], 2007) to central axes (as in Da sinistra and other, midsize formats) to allover grids composed of variously taller or wider rectangular areas in the larger works (as evinced by Obliquo policromo [Polychrome Diagonal], 1972, or Sei colori). Whether unique pleats or edge-to-edge armatures, the creases provide a rigorously linear foil to the painter’s comparatively variable, soaked-in signs. Indeed, these two orders of drawing—the one that he does with the canvas, and the one that he does on or more precisely in it—frequently make contact, as in Dalla terra al cielo or Obliquo rosa (Pink Diagonal), 1973, to take just two examples. But the former mode also underscores how much of the canvas remains untouched by the latter—like unmarked bars of a musical score. Importantly, as in the earlier Da sinistra, Griffa’s pastel tones encourage associations with femininity, as do the repetitive, “menial” actions of folding and marking the cloth supports. Here as elsewhere, the painter who would later claim to have lived the late-’60s moment as a “housewife” appears to identify with decidedly nonheroic—indeed, socially unrecognized—forms of embodied labor: practices explicitly grounded in repetitive, everyday routines (a housewife’s work is never done). (Much more could be said about the limits of this identification, and of the larger, decidedly uneasy entanglement of art, gender, and labor in the notionally “impersonal” abstraction of this period, and not just Griffa’s.)

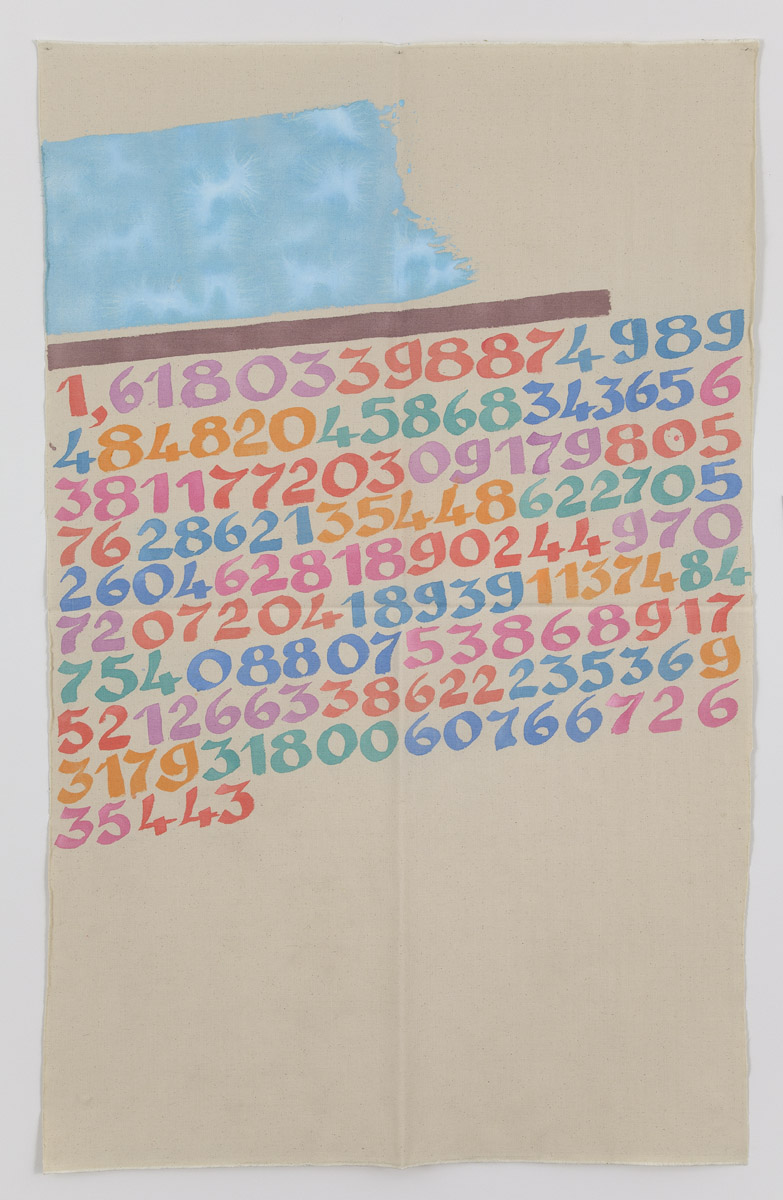

That we nonetheless remain within the domain of art—and a decidedly masculine canon—is clear from the long-running series “Alter Ego,” 1979–2008. Throughout that suite, and closely aligned with the artist’s interest in what he has called “the immense internal memory” of painting, Griffa’s “writing” is overtly citational, indeed intertextual. Represented in Geneva by Paolo e Piero, 1982 (in reference to Paolo Uccello and Piero Dorazio); Matisseria N.1, 1982; and DDB (Da Daniel Buren), 1997, the group also includes references to Yves Klein, Paul Klee, Joseph Beuys, and other figures the painter believes helped pave the way for him. This self-consciousness is not, to my eye, a good thing for Griffa’s art: The results too often reveal a stylized, somewhat precious quality that also undermines the recent paintings from the “Canone aureo” (Golden Ratio) series, 1993–, canvases inscribed with necessarily truncated fragments of the titular proportion in number form. (There were four such works in Geneva, from between the years 2012 and 2014.) Yet the homage to Buren in particular—a work whose repeating vertical stripes immediately conjure its dedicatee—does have the virtue of making explicit one of the limits of “anonymity” in art: Even ostensibly impersonal signs remain bound to historical individuals, who are conditioned in turn by a larger tradition. Griffa, one gathers, has known this all along.