Casey Kaplan

IGSHAAN ADAMS IS DISARMING US WITH QUIET ACTIVISM

by Gabriella Pinto

9 September 2016

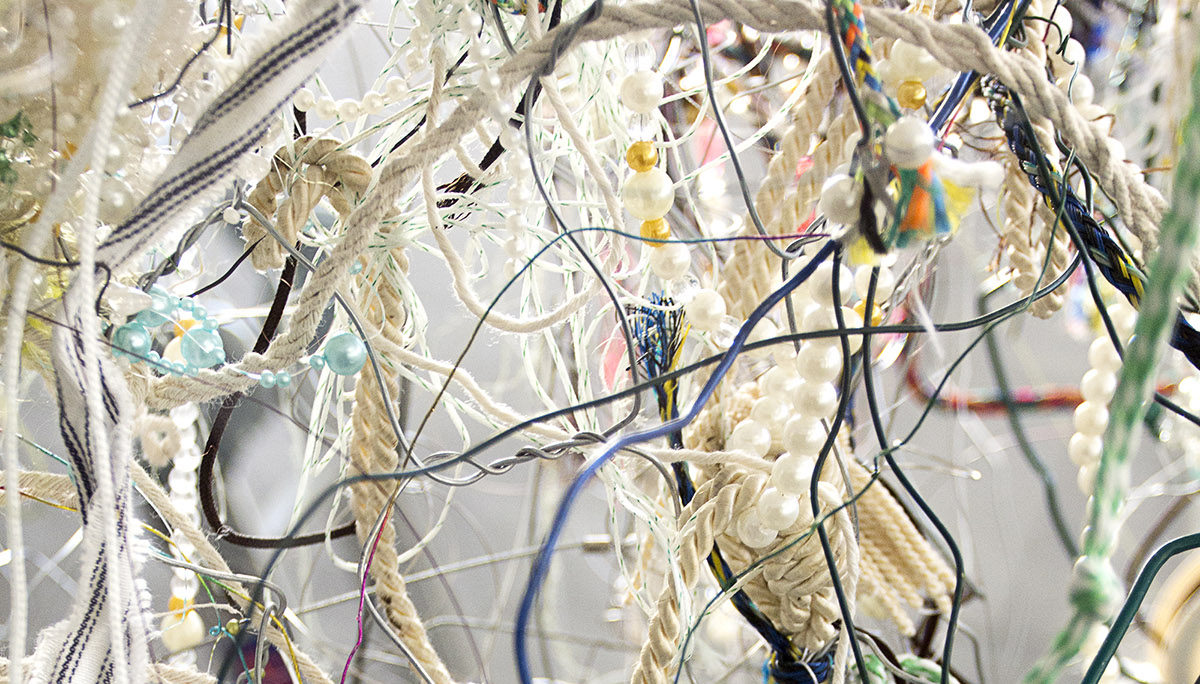

Igshaan Adams’ tapestries and sculptures made from string, beads, found fabric and steel delve into complex concerns about cultural hybridity. His latest exhibition, “Oorskot” at Blank Projects, explores the concept of ‘remnants’, which physically refers to his usage of discarded and excess material from previous works that have been reshaped into new forms.

Notions of death, decay and rebirth permeate the work, while green dominates the colour palette. “Culturally, the colour green is widely associated with quietude, health and vitality. In Islam, green is considered the most important colour, as it symbolises the lush vegetation of Paradise as well as the religion’s peacefulness, and it is recognised as the colour of the Prophet Muhammad’s banners and robes,” explains his manifesto. Igshaan’s work prompts quiet contemplation and inquiry into identity, beauty and their darker undercurrents.

How has your upbringing influenced both the kind of work you make and your creative process?

In terms of the kind of work – it all being material and texture based – I think I certainly grew up in a creative family. I grew up with my mom’s family, my grandparents and my mom’s sisters raised us. There were always creative projects in the house I grew up in, whether it was making banners for church or catering jobs, and I always thought I’d end up in the catering industry. It was about finding whatever was available within the environment. For instance I remember often going into the garden for instance and looking for sticks or using pieces of paper to make things out of nothing. That approach to making art stuck with me. Also, trying to change the material to appear as something else and elevate it in some way. I think I learnt that from my childhood.

You mentioned going into catering. What made you decide to become an artist?

My family was really poor. I applied for hospitality studies but it was three times as much as visual arts. It was a cheaper option and I was able to afford it with a bit of help from my aunt. I had to pay for the first six months. I was never really exposed to art so it was never an option until I was out of high school. I went to Cape College where I studied graphic design because I thought that would bring in money quicker and I’d get a job and find the independence I was looking for, but it didn’t really work out that way. I ended up becoming a gardener for many years working for my aunt in Hout Bay. In 2007 I applied for the Thupelo Workshop (organised by Greatmore Studio) and they offered me a scholarship to finish my studies. I finished my diploma in 2009, and that’s kind of where it started.

What inspired your latest body of work?

It’s a mixture of things. I was certainly inspired by what I saw in Panama when my partner and I visited at the beginning of year. Specifically, the plants in the jungle. I just enjoyed seeing these massive forms that are created. That stayed in mind throughout the process. I also think inspiration happens throughout the process as things develop and form.

Your artist’s manifesto talks about the work shifting from being tapestries on the wall to stand-alone sculptures. What brought that about and how has it furthered your investigation into line and texture?

The one work, “Oorskot,” which also carries the exhibition title, started this way. I’ve worked like this for the past few years. I’ve always had something in my studio, where I would try out all the crazy ideas which were meant for the dustbin, eventually. I can just do anything there and play with all the ideas I gave up on.

Eventually, something interesting started happening with this ‘thing’ I had. I started adding all the things I had on the floor which I’d accumulated from the very first body of work I did. I just kept all these off-cuts. There’s a little bit of most of the work I’ve ever made within this one piece. I didn’t start out with the intention of it being an actual work, just this thing that I wanted to explore.

What’s the relationship between the exhibition’s title and the themes of identity which you often explore?

First of all, “Oorskot” can also mean human remains in Afrikaans. It started out with identity. In 2013 got to do this performance with my father titled “Please Remember II,” and I realised that the reason why I felt like it literally changed my life was because I was able to kill something. Something died. Something to do with my identity which I no longer needed. It was something I needed to shed like an old skin.

So, what I liked with this word “Oorskot” is that it refers to these remains after death has occurred. I’ve not be able to confirm this but a friend of mine who’s Afrikaans seems think there’s a religious connotation to the word too. It refers to the remains after something has left you, like a soul, for instance.

It also means remnants, traces of stuff, which has also been a theme since my vinyl work in 2010. Within the exhibition, it’s not just about death occurring but also about the space that allows something new to spring out. There’s that too, I think.

Read the full interview HERE