Casey Kaplan

![]()

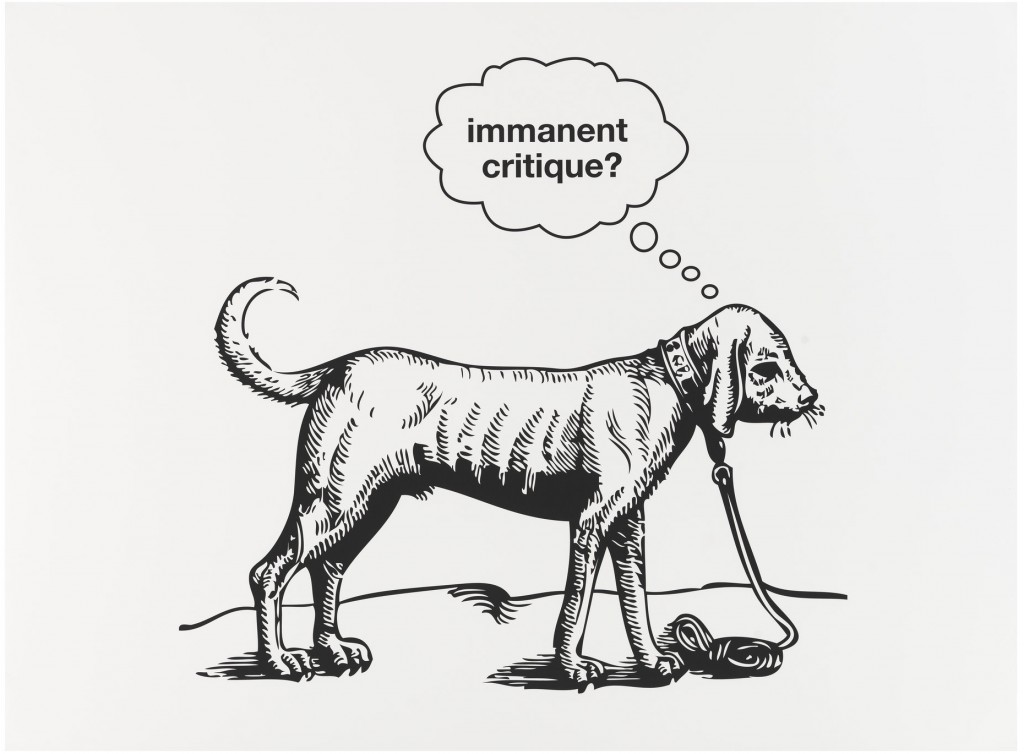

Liam Gillick’s Immanent Critique (2015) takes a phrase familiar to anyone who has struggled through the dense philosophical writings of 18th Century German think Immanuel Kant, and reduces it to a momentary thought in the life of a dog. The attribution of human thoughts and behaviors (walking and talking) to animals has been central to animated entertainment and puppetry for decades, yet while these images—static or moving—have largely either been directed towards children, or towards more irreverently “adult” thematics (from R. Crumb’s Fritz the Cat, to The Family Guy’s dog-character Brian Griffin), Gillick’s invocation of this trope is far more sophisticated and deadpan. It softly lampoons the tendency of pet-owners (and dog-owners especially) to bestow emotions and informed responses onto the beloved animals in their care, yet inserts a complicated philosophical notion that would be equally improbable of popping into the average human’s brain, much less that of a canine.