Casey Kaplan

![]()

Simon Starling

The story behind an artwork, in the artist’s own words

THE ENTHUSIASTIC ATTEMPTS in 1874 and 1882 to use observations of the transit of Venus to refine the measurement of the mean sun-Earth distance, the so- called “astronomical unit,” are perhaps best known for their failings. What is less well known is that cinema is, in large part, the illegitimate child of those 19th-century scientific exertions.

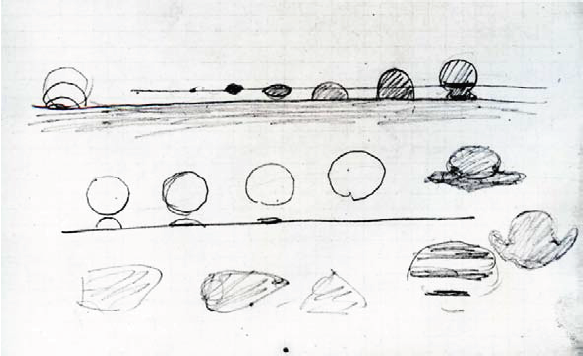

For many, Etienne-Jules Marey’s invention of the chronophotographic gun, the photographic rifle, marks a key genera- tive moment in the evolution of cinema. However, it is itself a direct descendant of an earlier device developed in 1874 by the French astronomer Pierre Jules Cesar Janssen: the revolver photographique. It was hoped that this telescope-cum-camera would allow for human-error-free analytical obser- vations based on repeated timed exposures made of the transit of Venus in geographi- cally remote locations. It soon became clear that the results of the 1874 observations were no more objective than those of the previous “nonphotographic” ones, the vari- ous revolvers having produced very differ- ent and therefore incomparable results.

While the 1874 transit. itself a quintes- sential, if reductive, cinematic experience -a shifty planetary protagonist projected by a vast bulb-sun onto the imaginations of an earthbound audience-may not have im- pacted greatly on our understanding of the solar system, it could certainly be argued that Janssen’s innovative approach to chro- nophotography had a huge impact on the future of cinema. It is little surprise, then, that one of the first films ever screened in public was the Lumiere brothers’ footage of Janssen himself arriving for the confer- ence of the Societe Française de Photog- raphie in 1895. Filmed in Lyon by Louis Lumiere the morning of June 15 as the con- ference delegates arrived by riverboat, the film, screened for the first time that very afternoon. shows a stream of well-dressed people walking down the gangplank onto the quay. Fittingly, perhaps, the first del- egate down the gangplank is Janssen.

The importance of this rare astronomical event to science has long since waned. but we now-seemingly in the dying days of celluloid-based cinema-have a chance to reconsider the historical and technologicalimpact of the transit. Together with a small film crew, I made a journey to the islands of Hawaii and Tahiti to observe and film the 2012 transit ofVenus as well as the sites of previous observations (Point Venus, Tahiti. in 1769, and Honolulu in 1874). Hawaii is also the death place of Captain James Cook (1728-79). who famously observed the distorting black-drop effect on the island of Tahiti in 1769-an effect that, in large part, led to Janssen’s use of chro- nophotography some 100 years later. The recording of the event (almost certainly the last time this might be done using cellu- loid film stock) will form the basis for the production of a film, Black Drop, about the relationship between the transit of Venus and the history of cinema, framed by the parenthesis formed by the 1874 and 2012 transits. In the final stages of filming, this complex drama will be played out in a 35 mm film editing suite, as an editor attempts to bring structure and understanding to a rhizomatic array of geographical locations. historical information, and still and moving images.